A Day That Will Live in Infamy

Regardless of age or circumstance, my father will always remember where he was when JFK was gunned down in Dallas.

My mother will never forget her feelings and her reaction, when her principal announced over the intercom at Charles E. Perry High School in Roseboro, N.C., "They killed Martin Luther King!"

While not as world changing or life altering, Jan. 13, 1999 is a day that will live in infamy for as long as I live—which is hopefully a long, long time.

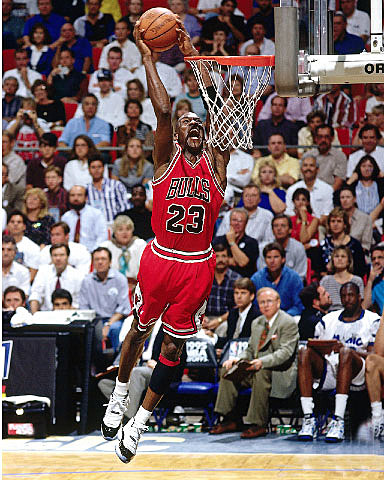

Three thousand, six hundred, fifty-two days ago—10 years—Chicago Bulls guard Michael Jordan, arguably the most influential sporting figure of the 20th century, announced his retirement from the NBA.

While he would return two years later for a two-year stint with the Washington Wizards, 1999 marks the end of "Air" Jordan—a legacy he carefully crafted along with the folks in Beaverton, Oregon (Nike).

The dichotomy that is Jordan is one that can fill much more than the space allotted here and that sometimes can be troubling.

On one hand you have the most charismatic, intimidating, fun, passionate, talented and skilled basketball player of all-time.

Jordan, a man who could sell practically anything, was the face of companies like Gatorade, Nike and Hanes.

Jordan, a man who could sell practically anything, was the face of companies like Gatorade, Nike and Hanes.

He had a kids' movie that spawned an inspirational staple of modern music—R. Kelly's "I Believe I Can Fly."

Gatorade even had a song that encouraged children to follow in his footsteps and "Be like Mike."

His love of the dramatic shot and acrobatic play made him adored by media and people who might not watch basketball. No one brought in the casual fan like M.J.

Jordan's on-the-court creativity and flare were monumental assets, juxtaposed and ultimately overcome only by his vanilla, generic social and political views off-the-court.

Certainly, Jordan did positive things for his birthplace, Wilmington, N.C. and in his adopted hometown Chicago.

But, he made it a point to avoid controversy and anything that may jeopardize his legacy—or more importantly his revenue stream.

At his alma mater—The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill—Jordan was asked several times to help contribute to a free-standing black cultural center.

To this date, folks with inside knowledge of the situation say that Jordan wouldn't give money to what became the Sonya Haynes Stone Center for Black History and Culture.

Carolina alums like Dre Bly and Stuart Scott helped pay for the building, but not Jordan.

Allegedly, Jordan didn't want to mingle in a controversy as steep and polarizing as the Stone Center.

In the early 1990's senatorial race between Jesse Helms and Harvey Gantt, the black mayor of Charlotte, N.C., veteran writer and columnist Sam Smith said Jordan had opinions and views that strongly coincided with Gantt.

In the early 1990's senatorial race between Jesse Helms and Harvey Gantt, the black mayor of Charlotte, N.C., veteran writer and columnist Sam Smith said Jordan had opinions and views that strongly coincided with Gantt.

But Smith said that when pushed to get on board and campaign for Gantt, Jordan gave his classic and often-quoted reply, "Republicans buy sneakers too."

It's that sort of lack of overall responsibility and morale obligation that makes Jordan such a brilliant, enlightening yet semi-tragic figure.

What makes Jordan's decision to not speak out when he had the world listening and moving off his every word is that he had much more pull than his predecessors.

Do you think, had Jordan made an overly political statement in 1992 against say Bill Clinton, he would be admonished in the same way Bill Russell, Kareem Abdul-Jabar and Muhammad Ali were?

Absolutely not.

This may seem unfair to guys like Jordan, LeBron James, Kobe Bryant and Tiger Woods, but it's not.

There is a common theme in literature, pop culture and history, whether it be the Bible or a Spider-Man comic book.

"To whom much is given, much is required."

Let's hope the next generation of athletes follow that axiom, not Jordan.